Published on Cāṇakya – The Indo Mediterranean Initiative

On January 16, 2025

The Resurgence of Corridor Diplomacy: Corridor Diplomacy has returned with Projects like India Middle-East Europe (IMEC) Economic Corridor as a focus of multilateral groupings.

India’s Rise as a Global Powerhouse: India is rising as one of the world’s largest powerhouses, with a workforce of one billion and a GDP that, by 2030, will be second only to that of the USA and China.

The West’s Declining Role in Corridor Initiatives: The absence of the West, and notably of Europe, from the game of corridor diplomacy, is simply a symptom of its descending political trajectory.

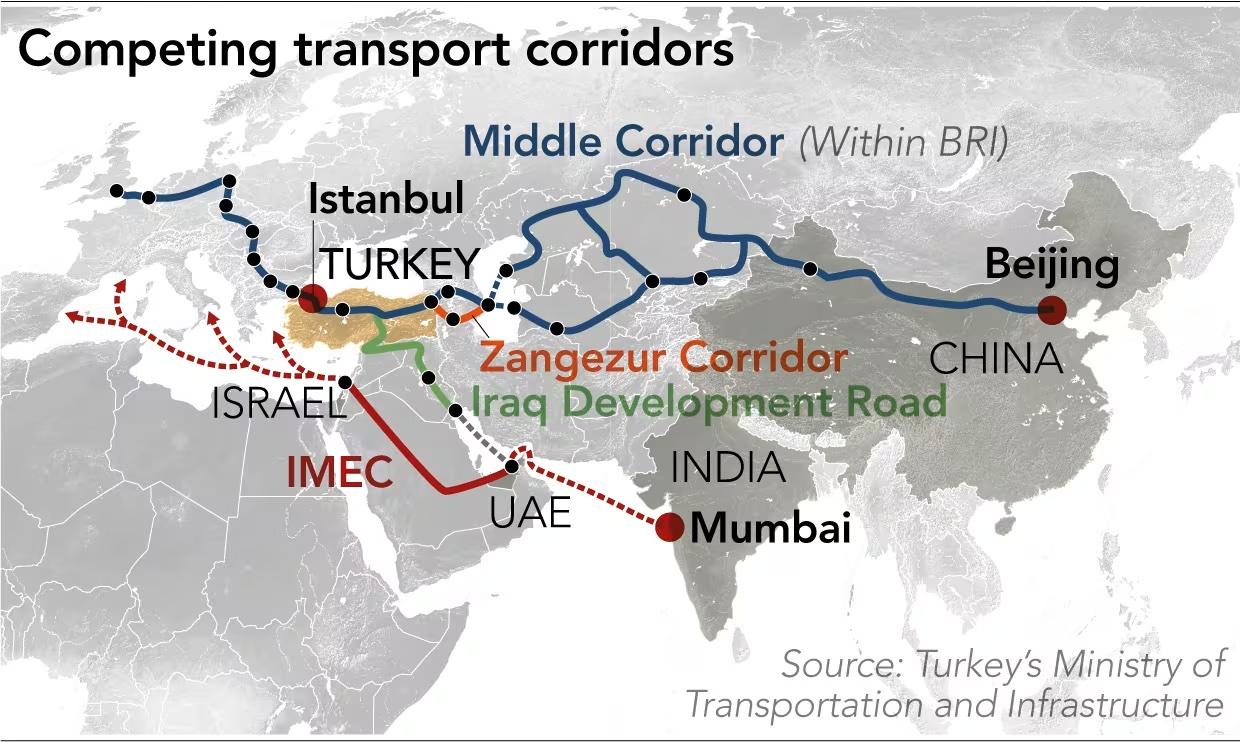

Corridor diplomacy is back. Vast networks of railways, ports, pipelines, and roads are again surging as instruments of influence, diplomacy, and strategy. While this is not a new concept—historically, successful empires consolidated their power by controlling critical trade routes—in the 21st century, the leveraging of large-scale infrastructure is becoming a defining feature of emerging powers’ strategies to advance their geopolitical goals.

The ambitious India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), announced at the G20 Summit in New Delhi in September 2023 is a case in point. By linking India, the Arabian Peninsula, and Europe, the corridor aims to streamline trade routes and reduce transit times by 40% compared to traditional maritime pathways like the Suez Canal, and project Delhi’s on its immediate neighborhood and beyond its region.

Many indicators tell us that India’s time has come. The country is rising as one of the world’s largest powerhouses, with a workforce of one billion and a GDP that, by 2030, will be second only to that of the USA and China. With IMEC, India positions itself as a key player in the global connectivity landscape, but also in an increasingly asymmetrical and multipolar international order.

New Delhi also views IMEC as a strategic foreign policy tool and a cornerstone of its long-term strategy to counter China’s expansionism in the Indo-Pacific region. By strengthening ties with Europe, the United States, and Gulf countries, the corridor seeks to solidify India’s geopolitical positioning. In addition, IMEC is also meant to connect the economic hubs of Europe and Asia, as well as existing regional cooperation initiatives which had either been encouraged or guided by the US. These include the 3 Seas Initiative (Baltic, Adriatic and Black Sea), the Greece-Israel-Cyprus cooperation in the Eastern Mediterranean and the India-Israel-United States-United Arab Emirates (I2U2) forum in economic and military domains.

Notably, such schemes of alliances see a major exclusion in the wider Mediterranean space: Turkey. Relations between Ankara and the US have been strained over the course of the last decade, due to Erdogan’s pivot away from the West as well as American support to Kurdish fighters in Syria and Turkey’s acquisition of the Russian S-400 air defense system and the contextual exclusion of the country from the F35 program. As a result, with the US and NATO losing trust in Ankara as a reliable partner, Turkey has been sidelined from these regional integration initiatives.

Turkey’s position on IMEC has never been warm. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan declared, on the sidelines of the 2023 G20 summit where the plan was announced, that “without Turkey there is no corridor”. Indeed, Ankara perceives IMEC as a direct challenge to its historical role as a vital hub for goods transport between Europe and Asia—a role it has cultivated for centuries due to its unique geographic position. In response, the Turkish government unveiled the Development Road Project — formerly called Dry Canal — in 2023, an ambitious initiative aimed at establishing a 1,200-kilometer network of railways and highways linking the Persian Gulf to Europe via Iraq and Turkey.

According to Ankara, this project offers a shorter and potentially more cost-effective alternative to IMEC and other existing routes, such as the Suez Canal, as it does not involve any disputed territory and integrates with existing corridors – such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Middle Corridor. Moreover, Turkey aims to leverage the economic benefits that will derive from the initiative to further strengthen its influence over its southern neighbors, especially in Iraqi Kurdistan and the broader Levant following the demise of the Assad regime.

In a Middle East increasingly characterized by instability and internal conflicts, Turkey stands out as an example of relative stability, reinforcing Ankara’s position as a central player in global trade and corridor diplomacy. Moreover, the country’s strategic location at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East not only enhances its logistical significance but also positions itself as an essential dialogue partner between East and West.

Of course, corridor diplomacy comes at a price.

Being the cornerstone of China’s expansionist strategy in Africa and Asia, the Chinese BRI is the natural benchmark of any such initiative. Through its large-scale infrastructure projects, Beijing has garnered the support of more than 150 participating countries for a narrative of an alternative model of global development, distinct from the West’s.

Although the BRI has profoundly reshaped the geopolitical and economic landscape of much of the African continent, the promises of prosperity have not fully materialized: in many cases, the benefits for recipient countries have been temporary or overshadowed by significant challenges. Several emerging nations, burdened by debt to China for grand infrastructure projects, have found themselves compelled to relinquish control to Beijing of the very assets they built.

In addition, engaging in corridor diplomacy implies gaining a direct, often undesired stake in multiple political cauldrons, with ongoing conflicts and political instability presenting a constant threat. IMEC traverses geopolitically volatile regions, with Israel’s Haifa port being the link between the Gulf and Europe via Piraeus, Athens. The success of IMEC also depends on the normalization of bilateral relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia, amid the ongoing war in Gaza and the evolution of Iran – Saudi strategic rivalry, which affects the Strait of Hormuz, a critical access point to GCC ports.

Conversely, Turkey Development Road Project relies on Iraq stability. With highways and railways linking the southern Great Faw Port in Basra governorate to the Turkish border in the north, pockets of IS insurgents, Iran affiliated militias, PKK strongholds, and ongoing guerrilla all but pose pressing threats in terms of infrastructure security.

The absence of the West, and notably of Europe, from the game of corridor diplomacy, is simply a symptom of its descending political trajectory. In the long term, this inertia will bear costs in terms of strategic autonomy. As just underlined by incoming US Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, we are going to live in the world where much of what matters to us daily will be dependent on other countries allowing us to have it or not. And yet, even for a passive bystander, redundancy of trade routes is good news. Competing large-scale infrastructural initiatives means risks would be spread across different regions. Crucially, diversifying trade routes might reduce overdependence and significantly reduce the leverage of economic coercion and other unfair trade practices. Redundancy means resilience, and resilience means flexibility in the face of the unforeseen.

Articles & Media Mentions